The Boy and the Heron: The (Sort of) Final Miyazaki Film

Saying goodbye is never easy. Some artists leave behind a legacy of fantastic films with one final swansong fully intended as their magnum opus. For others, they may unfortunately just… stop one day. The mind of Hayao Miyazaki has never been one to back down from the industry of animated film, each and every film of his feeling distinct and yet unmistakably a work of his own. No one else could have made The Boy and the Heron, a film which truly feels like Miyazaki is saying goodbye to a world of cinema and, in a way, Studio Ghibli. However, the director has since returned to the studio with ideas for a new film, as shown in an interview with veteran Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki.

Talks of Hayao Miyazaki’s retirement go as far back as 2005-2006, during the production of Tales from Earthsea, directed by his son Goro Miyazaki. The director has never succumbed to retirement since, and his return to the studio this time probably won’t be the last time we witness his “retirement”.

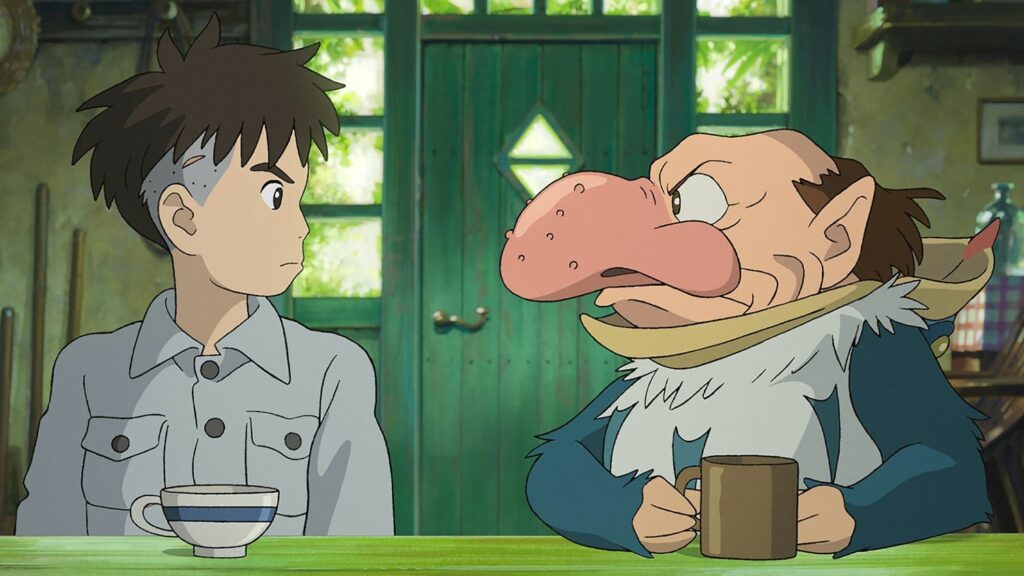

The Boy and the Heron tells a profound story about a boy named Mahito growing up in war-torn Tokyo, moving to a more rural area once his mother perishes in a hospital fire and his father remarries his late wife’s sister Natsuko. From here, the film seems to take cues from multiple different Ghibli films, namely Spirited Away, which it resembles the most. However, that’s not to say the film copies or insists upon the previous work of Miyazaki consciously or obnoxiously. Miyazaki is as Miyazaki’s been, creating heartfelt films about a lost character finding themselves in a strange new land, discovering more about themselves that they didn’t know they’d needed all this time.

The first half of the movie is incredibly captivating and tragic; Miyazaki hooks the viewer with the melancholy eccentricities displayed by Mahito and the tragedy he faces, as well as keeping alive the mystery of the blue heron bird that lingers throughout the countryside, taunting him and luring him to the eerie tower over the river. The audience can really connect with his struggles, really rooting for him and hoping he’ll find solace in something in this new land, but it’s clear he’s never truly been the same since his mother passed away in that fire.

The second half of the movie relies upon Miyazaki’s tactic of an open-ended adventure, wherein Mahito finally answers the call of the blue heron and explores this new world within the tower. The characters he meets and the locations he travels to all feel distinct and dynamic, intrinsic to each others’ existences. They’re tied together really well, and it really does feel like the inherent stability of this strange land insists upon the fact that these characters exist right where they exist–something explored in the later scenes of the film. It’s a powerful mode of storytelling, though Miyazaki’s tactic does play down some of the important elements of the film a bit as a result. It’s common for Ghibli films to be open-ended and vague, and sometimes the viewer can easily derive meaning from what a scene’s purpose is. However, with a film as packed as The Boy and the Heron, employing so many of Miyazaki’s methods of direction, it almost feels too vague at times in this new world. As the first half of the film is grounded in reality, it’s easier to tell what a character is feeling or what they’re planning on doing based on their body language and actions. However, this new world requires a bit more exposition and directness to fully understand what some of its components really mean.

The Boy and the Heron is now playing in theaters worldwide.